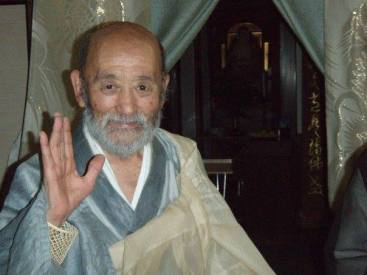

I just learned from a dear Dharma friend that our great teacher Harada Tangen Roshi, of Bukkokuji Temple in Obama-shi, Fukui-ken, has passed away at the age of 93.

Goodbye, Roshi-sama.

There are no words to express my gratitude for your teaching. For the opportunity to have sat, worked, eaten, chanted, bowed, begged, and slept in your presence. To have received your teaching through body and mind. Wagamama though I was and continue to be, your teaching and presence still ring through my being.

With one hand, fire. The hara, the shout. If you set out to accomplish it, you will accomplish it. If you do not set out to accomplish it, you will not accomplish it.

And with the other hand, water. The smile, the easy laugh. Subete yoshi. “It’s all good.”

May I hear, everyday, every wagamama moment, you ringing me out of your room.

And may everyday, every moment, I return to your room again and touch my forehead to the floor: My name is Jiryu. My practice is shikantaza.

Thank you, Roshi-sama.

We have the expression, ichi tantei (‘one doing’). NOW. NOW. This is ichi tantei. A teacher is one who clearly reveals this to the student. “Reality is not off someplace else, away from right now and here. NOW. HERE. Don’t be careless. Don’t be off guard.” The teacher points out the path, the direct route, in the way most appropriate to each student. With this direction, the student can truly practice the most treasured, straight path.

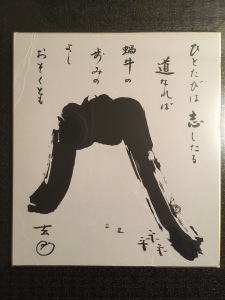

My favorite Roshi-sama calligraphy, the snail climbing Mt. Fuji

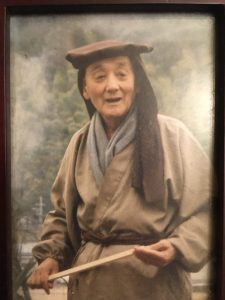

One of my many fond recollections of Roshi-sama, from Two Shores of Zen and offered with appreciation in his memory.

Precisely at 10:15 am Roshi-sama starts down the stairs from his room, with Daiko-san attending close behind him, swishing through the hallway towards the hondo in the ornate vestments I think of as his “Sunday robes.” Taking the cue, Ankai-san scurries up the ladder and starts pounding the drum, slowly at first, then gradually building speed. He hits hard and loud, with martial ferocity, but the sound is flat, lacks the fullness that sometimes reverberates through the taiko.

“Dame!”, no good!, Roshi-sama shouts furiously as he nears the drum, breaking into a run out of the solemn procession of two and waving his arms at Ankai-san, who stops and climbs meekly down from the ladder. Ripping the drumsticks from Ankai-san’s hands, Roshi-sama scrambles up the wobbly ladder himself, his floor-length robes tangling around his legs and his elderly body heaving for breath. The assembly seated below watches anxiously, and Daiko-san rocks nervously at the bottom of the ladder, poised to catch his frail teacher as he falls.

High up in the drum alcove, Roshi-sama strikes the drum once. It sounds flat, at least as dull as Ankai-san’s. From my place on the tatami floor, I look up at Roshi-sama and feel a little embarrassed for him. I hope he wasn’t trying to make a point about the drum. He’s an old man, I remind myself, and just because he’s enlightened doesn’t mean he has the strength to hit a drum.

Unfazed, Roshi-sama hits the drum a second time. The clear sound shakes the sliding wooden doors, reverberating through the weave of the cool tatami. Good hit, old man, I think.

He strikes a third time. An explosive, expansive boom fills the temple, not so much shaking things as settling, silencing them. The sound blankets my mind with its clarity and weight, snapping me into a new, immense consciousness. My whole field of awareness smoothes out, crystallizes, and fills to overflowing with the vastness of my being.

Roshi-sama, now himself a stillness that flows through the stillness of a hall that is no longer any other than my body, descends from the alcove. He crosses his legs under his robes at his seat, rests a moment—complete unmoving—in his place, and then addresses the assembled monks and laypeople.

“I hit the drum three times just now. The first time I hit it like Ankai-san had. Ankai-san, your hits were no good! Your arm was extended, your body was bent, you were off balance. The way you were standing, it was impossible to hit the drum well.

“The second time, I hit it correctly. There are ways to do things. When you do things in certain ways, it is easier to become one with them. When your body is close to the drum, you can hit it with ease. When an action comes from your hara—when you hold the drumstick with your hara—the result is always excellent. We must learn this in our practice, to fully use the hara in everything we do. That is the way I hit the drum the second time: I hit it correctly, the way it should be done.

“The third time—did you hear the third hit?—the third time I just became one with the drum. The drum, the old teacher, no separation.”

I am in awe of him, absorbed in his sweet spell.

Dear Jiryu,

We did a memorial this morning at Santa Cruz Zen Center. Kokyo spoke with the same deep reverence and power as you have here. May our practice be of benefit to your great teacher.

Bowing,

Neti

ThyLejren, 14 March 2018

Om Gate Gate Paragate Parasamgate Bodhi Svaha

I remember (1984) Roshi-Sama especially as somebody who was able to reach great heights while also being a very ‘normal’ human. I once had the honor to receive a blow with the kyosaku from Roshi himself. After more than 30 years I can still feel the trembling power in my shoulder: it is EARTHY power. Your beautiful story of the drum I find also typical Roshi-Sama. I suspect the first beating was NOT deliberately poor – but Roshi retook himself and turned it into an even stronger teaching. As he did when in 1945 he was not allowed to make kamikaze because that very day Japan surrendered. ‘So then I became a monk’.

I’ve been practicing (nearly) every day since I left Bukkokuji – until a year ago, when one knee started hurting too much. Tried several treatments to no avail. One morning at Bukkokuji there arrived an ambulance. Roshi was carried there on a stretcher. Back the next day, both his legs in tight bandages. Sitting in full lotus again in a week or so. Must find a Japanese doctor ..

Thank you Jiryu

Ralf van der Schaar (NL, DK

Thank you for this beautiful reflection on a powerful life.

Wonderful words for your teacher. I loved your description of him in the book. Made him seem fierce and tinder. Exactly what a good teacher should be.

*tender although maybe tinder works too

I too was trained by old-school, Japanese Zen masters who placed strong emphasis on understanding/actualizing hara. This awareness of hara and its importance in Zen practice I notice is, sadly and rarely, ever mentioned in the many talks I’ve heard over many years by American Zen teachers. Why is this? Something so vital to Zen practice, lacking the emphasis it truly—if American Zen is to survive on this soil—needs.

Hi! I am putting together a book about Roshi-sama, to include stories by practitioners. I came across your story. Can I put it in my collection for possible use?

Hi Ron, yes of course, and please email me jiryu at sfzc dot org.